Welcome travelers!

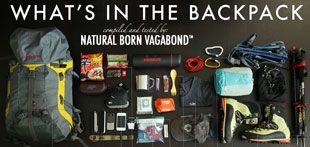

Natural Born Vagabond™ is a bilingual (English and Polish) site devoted to travel photography and journalism. Here you can find images and articles from our remote travels. The ambition of the creators is to share the best stories with those who crave wilderness and adventure. If you would like to share your opinions or travel stories please contact us via e-mail.

Featured

Natural Born Vagabond™

Wild game in the Serengeti

“Honey, I think I just saw an elephant in the backyard!”

Our safari in Tanzania’s renowned Serengeti National Park started right after our successful ascent of Mount Kilimanjaro in August 2012. Indeed, we were basking in the afterglow of the accomplishment of conquering Africa’s highest mountain (which also doubles as a volcano) — still inured to the conditions of the mountain (i.e. no running water, no toilets, dust and dirt all over our clothes, etc.) — when we quickly transitioned into a new and pampered adventure, absorbing the beauty of Africa’s flora and fauna from the comfort of a 4×4 Toyota truck and replacing our humble tents with 5-star luxury villas.

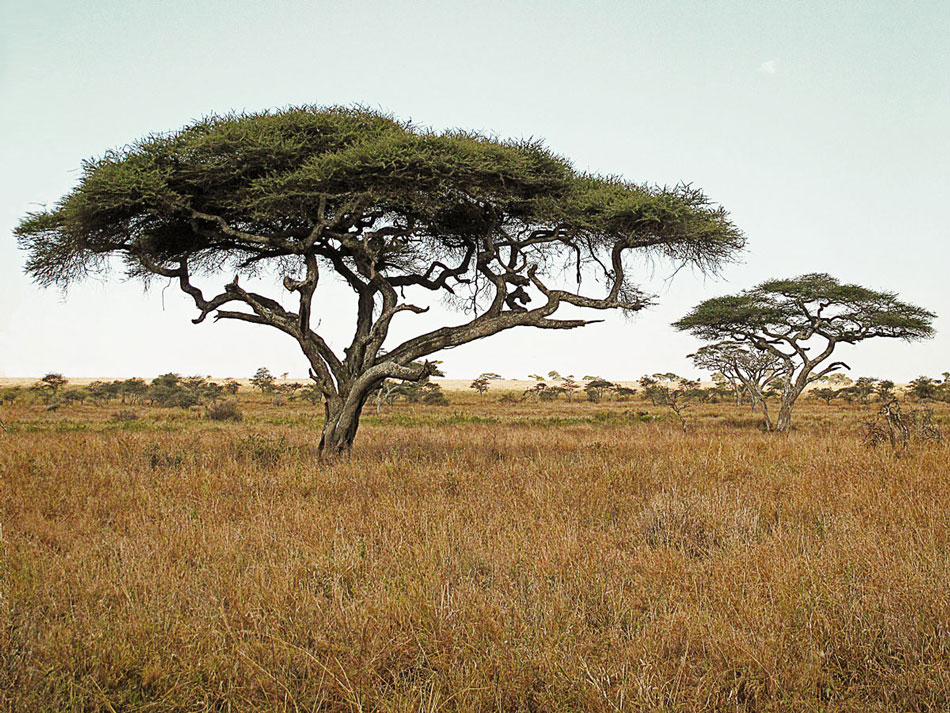

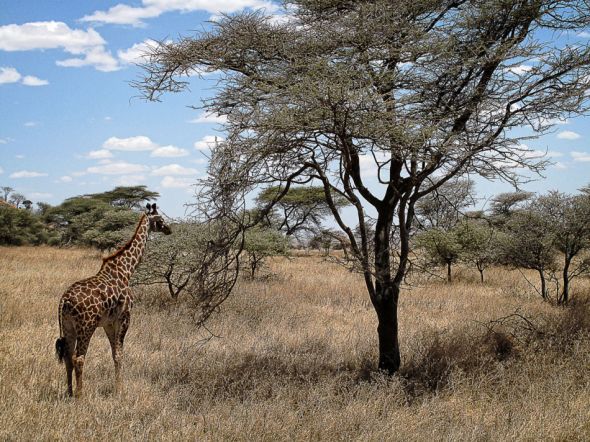

The safari portion of our African adventure began when we were picked up from our guest house in Arusha and were driven 120 km southwest to Lake Manyara National Park. The lake lies 960 meters above sea level and is a popular and convenient hangout for all types of birds, including cormorants, flamingos, pelicans and storks to name just a few. The park is also home to large land mammals, including baboons, blue monkeys, elephants, giraffes, hippopotami, hyenas, impalas (which we later saw served grilled on roadside street stalls), jackals, lions and wildebeests. And of course, there were many other denizens of the Savannah unknown to us (making us rue the moments when we did not pay more attention to the wildlife shows on television when growing up), but whose images we recall as vividly as the afternoon Savannah sun. All the creatures seemed to enjoy their environment. The elephants and hippopotami seemed most at home in water or frolicking in the mud. Impalas, on the other hand, were masters of the grassland, racing from one patch of grass to another as fast as gust of wind. And of course the lions, as kings of the jungles (though they really live in grassy terrains), without enemies or fear, lazed in the shadow of the trees that occasionally dot the landscape to evade the scorching African sun.

Our experience at Lake Manyara National Park was also interactive as we had the chance to continue with our climbing ways by scaling oversized cathedral termite mounds. Though much smaller than Kilimanjaro, coming up close to these marvels of engineering was awe-inspiring — as much as they seemed alien and out of place — in their own way. However, the stars of the show in this park were the trees: aged mahogany oaks, spread-crown acacias and baobabs, which also go by the name “the tree of life”. Baobabs are also bearers of a strange velvety fruit the size of a coconut weighing some 1.5 kg that are known colloquially as “monkey bread”. The baobabs are amongst the oldest living organisms on Earth, with some supposedly near 6,000 years old. With such history (with the oldest baobabs multiples older than the oldest cedars in Lebanon’s Cedar Park), they merited hugs (that would put a tree-hugger to shame) and a countless photos to capture such a unique specimen of nature that exudes unspoken ancient wisdom. (Babies fed a mixture of the tree’s bark and water are said to grow up strong and powerful according to local folklore.) The portliness of the trees (one has been measured with a circumference of 47 metres) and their tricky appearance made Antoine de Saint-Exupéry (author of “Le Petit Prince”) write the following warning to the free-running youth growing up in Africa: “Children,” I say plainly, “watch out for the baobabs!”

We spent our first night at the Serengeti Serena Safari Lodge, an enchanting resort with fairy tale-like villas (based on traditional Maasai motifs). So seamlessly is the resort blended into the wilderness that we were told to not walk alone in the dark, lest we might encounter wild animals as we passed from one point to another. At first, such warnings did not seem legit — probably just part of the marketing ploy to give guests a sense of a “true wilderness” experience. However, as we walked in the dark that night from the restaurant back to our villa and came up close to wildebeests chewing on leaves adjacent to us — causing us to tremble in fear — we then recognised the merit of the advice. If not for that near eye-to-eye encounter with the massive creature — who are known to put up valiant battles against preying lions — we would not have realised just how much our villa was integrated into the wilderness. And perhaps it was this close encounter that spooked our minds into hearing all kinds of noises in the dark that night and throughout the rest of our stay.

The following morning, while brushing our teeth and watching the sun rise over the Serengeti park from the villa terrace, we spotted several elephants roaming around our backyard. They were so close that we were lucky to have not panicked and ducked under our bed sheets. Instead, we remarked, “Honey, I think I just saw an elephant in the backyard!” and continued with working on our dental hygiene like zombies. But unlike last night’s encounter with the wildebeest, the elephants were in full sight as they casually lounged in the villa garden and enjoyed themselves feeding on the tree leaves. They were so close that we could have literally thrown a pillow (or a toothbrush) at them — if only we had the gumption! But who in their right mind would want to rile a creature that can turn you into a pancake in one step?

Over next couple of days we visited the Ngorongoro Crater — the world’s largest inactive, intact and unfilled volcano caldera — that has in modern times become a playground for many of the large land animals of Africa. The caldera, which was formed some 2 to 3 million years ago, is 19 km wide and 600 metres deep. Its remaining rim has an average elevation of 2,316 metres and estimates of the volcano’s original height range as high as 5,800 metres, putting it on par with Kilimanjaro. We also discovered here that zebras — like many in the animal kingdom (and especially dogs) — enjoy a good whiff of each others’ butts. We also heard some interesting theories behind the stripe patterns on zebras, including the seemingly incredulous phenomenon that such patterns create gentle winds on the surface of their skin to keep them cool from the Savannah heat. Right. But the “highlight” was observing three lionesses dining on a wildebeest next to the road. It was a sight not for the faint of heart: The predators faces appeared as crimson masks while they gnawed into the belly of the subdued beast. We also did manage to gain a peak at the rare white rhinoceros, but from a far distance. It was only with the benefit of our binoculars and zoom feature of our camera that we verified that the tiny dark spot on the horizon was indeed the rare and elusive white rhino.

Even between one viewing destination to another we found adventure. It was a common site to see Maasai children with painted faces asking for donations in exchange for posing for photos with tourists travelling the safari circuit. And animals were as abundant and available to be seen on the road as in the parks. We saw elephants wandering alone or in packs, gazelles, hyenas, ostriches (beep beep), lions, and and families of warthogs, some of whom would become prey in the hierarchy of the food chain. And the geographic and climatic beauty of nature was on display as well, with islands of rock formations known as kopjes — translated as “little heads” in Afrikaans — sticking out amongst the vast sea grass. Finally, we were blessed to see countless dust devils and Savannah (dust) tornadoes as the weather in August seemed ripe for producing these wonders of nature. (Unlike the tornadoes of North America, Savannah tornadoes are spawned in dry weather and their size and scale are limited.) We even drove through a few of these brown vortexes which made us feel like we were storm chasers on the hunt for tornadoes, but in our case with mild versions of twisters. And just like the ephemeral vortexes, our African adventure soon also disappeared into the Savannah horizon, but not to be forgotten.

Thanks to Sandra and Gerrit for organising this amazing adventure, and to Alice and Thore for great companionship on the trip!