Welcome travelers!

Natural Born Vagabond™ is a bilingual (English and Polish) site devoted to travel photography and journalism. Here you can find images and articles from our remote travels. The ambition of the creators is to share the best stories with those who crave wilderness and adventure. If you would like to share your opinions or travel stories please contact us via e-mail.

Featured

Natural Born Vagabond™

The Missing Chapters — Sarajevo, Bosnia Herzegovina

‘What’s up with you Balkan people? I’ve never got a chance to study your countries: at school, all my teachers skipped the chapters about you saying your history is too complicated…’ I looked expectantly across the puzzled gazes of my students who came from all over the ex-Yugoslavia. Despite the recent conflicts between their countries, we were all living together under the same roof.

Even though I had been teaching in Macedonia for a few months, my impression of the Balkans was still fragmented. That’s why I decided to spend a week every two months in each Balkan state.

By Francesca Mauri.

Latin Bridge – photo by Francesca Mauri

I started with Bosnia and Herzegovina. Two of my Bosnian students gave me a ride on a snowy night to Sarajevo. One of them was Tarik, a bubbly man with warm, honest eyes who took advantage of the many hours ahead of us to tell me about his country and the three ethnic groups inhabiting it: Bosniaks, Serbs and Croats. He is a Bosniak, a Bosnian Muslim who, despite living part of his childhood during the war and spending six months in Sarajevo under the siege, is still in love with his city and has lived there ever since.

‘Remember to drink the water from Sebilj, the fountain in Baščaršija before you leave so that, if it’s God’s will, you’ll come back to Sarajevo!’

These were the words he left me with when they dropped me off at the doorstep of my hostel. I turned to steal a look of the city; however, the darkness of the night, even in the glow of the Catholic Sacred Heart Cathedral, was too thick to distinguish anything.

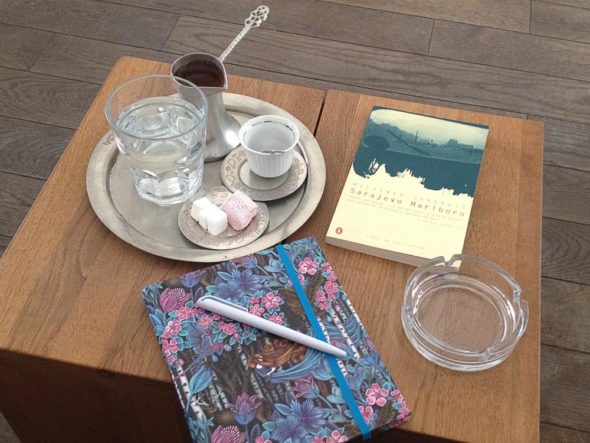

I had to wait until dawn to see Sarajevo. I bumped into it in the dimly lit cafés which even in the early morning are full of smoke and smokers. I followed it on dusty trams, travelling alongside elderly women who peeked at me underneath their headscarves and held me hostage with their mysterious chit-chat in Bosnian. Melancholic Sarajevo waved at me from the open windows of abandoned buildings, from the burned domes of palaces which used to make the passerby’s head spin.

Sebilj Fountain

In the following days I learnt about the longest siege in modern history and the deep sufferance endured by Bosnians.

On my last afternoon I met up with Tarik near the Miljacka river. In front of a cup of Bosnian coffee he gave me the history lesson I had been missing for so long, a history which is tightly intertwined to his own. In September 1992 when he was nine years old he escaped from besieged Sarajevo by crossing the city airport runway at night. Despite the risk of the Chetniks’ bullets, Tarik and his family managed to seek refuge in their hometown Ilidža.

‘Not everyone was as lucky as we were…And still what I remember the most about the siege is that people kept their dignity… Life didn’t stop even if death had become part of our daily routine, it was always hunting us from the hills while we were collecting water, buying bread or going to school. Sure, humans are humans and some took advantage of the war to make money. However, most of us helped each other, there was a sense of community: my mother shared flour and sugar with the neighbours even if we didn’t have much ourselves…’

According to Tarik, the strongest weapon people in Bosnia and Herzegovina used to resist during the conflict was the sense of humour they are famous for and which luckily does not get lost in translation. After exchanging our Do viđenja as goodbyes, I walked back along the river. Like the fog over the Miljacka, the past of Sarajevo covers the city like a blanket.

Alifakovac Cemetery – photo by Francesca Mauri

Preserving time and protecting the present is a collective mission in Sarajevo, a rule to respect even when visiting: slowing down is required, one cannot run in the streets of Baščaršija without knocking down the artisans’ stalls. Sarajevans gather every day around café tables to tell their jokes, as if there were always time to talk about life and death, laugh and be together. As if they were rewriting the missing chapters of their history.

Text and photography by Francesca Mauri.

Natural Born Vagabond™, June 2019